Why the Death Rate Was So High in Hatshepsut's Family?

| [a] | |

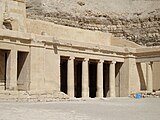

Hatshepsut'southward Temple | |

| Shown within Egypt | |

| Location | Upper Egypt |

|---|---|

| Region | Deir el-Bahari |

| Coordinates | 25°44′17.8″N 32°36′23.7″East / 25.738278°Due north 32.606583°E / 25.738278; 32.606583 Coordinates: 25°44′17.8″N 32°36′23.7″East / 25.738278°Due north 32.606583°E / 25.738278; 32.606583 |

| Type | Mortuary temple |

| Length | 273.v thou (897 ft) (Temple)[2] 1,000 m (iii,300 ft) (Causeway)[3] |

| Width | 105 g (344 ft)[2] |

| Summit | 24.5 yard (80 ft)[2] |

| History | |

| Architect | Unclear, possibly: Senenmut, Overseer of Works Hapuseneb, High Priest |

| Fabric | Limestone, sandstone, granite |

| Founded | c. 15th century BC |

| Periods | Tardily Bronze Age I |

| Cultures | Egyptian, Coptic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1827–present |

| Condition | Reconstructed |

| Public access | Express |

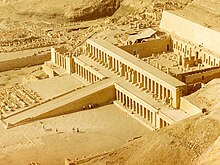

The Temple of Hatshepsut (Egyptian: Ḏsr-ḏsrw meaning "Holy of Holies") is a mortuary temple built during the reign of Pharaoh Hatshepsut of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.[b] Located contrary the city of Luxor, information technology is considered to exist a masterpiece of ancient compages.[c] Its three massive terraces ascension higher up the desert flooring and into the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari. Her tomb, KV20, lies inside the same massif capped by El Qurn, a pyramid for her mortuary complex. At the edge of the desert, 1 km (0.62 mi) due east, connected to the circuitous by a causeway lies the accompanying valley temple. Beyond the river Nile, the whole structure points towards the awe-inspiring Eighth Pylon, Hatshepsut's most recognizable improver to the Temple of Karnak and the site from which the procession of the Cute Festival of the Valley departs. The temple's twin functions are identified by its axes: on its main eastward-w axis, it served to receive the barque of Amun-Re at the climax of the festival, while on its due north-south axis it represented the life cycle of the pharaoh from coronation to rebirth.

Construction of the terraced temple took place between Hatshepsut'due south seventh and twentieth regnal yr, during which building plans were repeatedly modified. In its design it was heavily influenced by the Temple of Mentuhotep Ii of the Eleventh Dynasty built six centuries before.[d] In the organization of its chambers and sanctuaries, though, the temple is wholly unique. The chief centrality, normally reserved for the mortuary complex, is occupied instead past the sanctuary of the barque of Amun-Re, with the mortuary cult existence displaced south to form the auxiliary axis with the solar cult circuitous to the northward. Separated from the main sanctuary are shrines to Hathor and Anubis which lie on the middle terrace. The porticoes that front end the terrace hither host the most notable reliefs of the temple. Those of the trek to the Country of Punt and of the divine nascence of Hatshepsut, the backbone of her case to rightfully occupy the throne equally a member of the royal family and as godly progeny. Below, the lowest terrace leads to the causeway and out to the valley temple.

The state of the temple has suffered over time. Two decades afterwards Hatshepsut's death, nether the management of Thutmose III, references to her rule were erased, usurped or obliterated. The campaign was intense but brief, quelled after 2 years when Amenhotep II was enthroned. The reasons behind the proscription remain a mystery. A personal grudge appears unlikely every bit Thutmose III had waited xx years to act. Mayhap the concept of a female king was abomination to ancient Egyptian society or a dynastic dispute between the Ahmosid and Thutmosid lineages needed resolving. In the Amarna Menstruation the temple was incurred upon again when Akhenaten ordered the images of Egyptian gods, peculiarly those of Amun, to be erased. These damages were repaired after under Tutankhamun, Horemheb and Ramesses 2. An earthquake in the 3rd Intermediate Menses caused further harm. During the Ptolemaic period the sanctuary of Amun was restructured and a new portico built at its entrance. A Coptic monastery of Saint Phoibammon was built between the 6th and 8th centuries AD and images of Christ were painted over original reliefs. The latest graffito left is dated to c. 1223.

The temple resurfaces in the records of the modern era in 1737 with Richard Pococke, a British traveller, who visited the site. Several visitations followed, though serious excavation was not conducted until the 1850s and 60s under Auguste Mariette. The temple was fully excavated betwixt 1893 and 1906 during an expedition of the Arab republic of egypt Exploration Fund (EEF) directed by Édouard Naville. Further efforts were carried out past Herbert Eastward. Winlock and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) from 1911 to 1936, and by Émile Baraize and the Egyptian Antiquities Service (now the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA)) from 1925 to 1952. Since 1961, the Shine Center of Mediterranean Archeology (PCMA) has carried out extensive consolidation and restoration works throughout the temple.

Design [edit]

The temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari

Temple programme: ane) entrance gate; 2) lower terrace; 3) lower porticoes; 4) ramps; 5) center terrace; half dozen) heart porticoes; 7) north portico; 8) Hathor shrine; 9) Anubis shrine; 10) upper terrace; 11) festival courtyard; 12) Amun shrine; 13) solar cult court; and 14) mortuary cult complex.

From her accession to the throne, Hatshepsut renewed the human activity of monument edifice.[17] The focal point of her attention was the city of Thebes and the god Amun, by whom she legitimized her reign.[10] [18] [19] The preeminent residence of Amun was the Temple of Karnak[20] to which Hatshepsut had contributed the 8th Pylon, two 30.5 m (100 ft) alpine obelisks, offer chapels, a shrine with two further obelisks, and statues of herself.[ten] [21] Facing Karnak from across the river Nile, she built a mortuary temple against the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari.[22] The pinnacle of her architectural contributions,[22] information technology is considered to be among the peachy architectural wonders of the ancient world.[9] [11]

At its far eastern end, lay a valley temple followed past a i km (0.62 mi) long, 37 m (121 ft) wide causeway, which likewise hosted a barque station at its midpoint, that led to the archway gate of the mortuary temple.[3] [23] [24] Hither, 3 massive terraces rose in a higher place the desert floor[24] and led into the Djeser-Djeseru or "Holy of Holies".[10] [25] Nearly the whole temple was built of limestone, with some ruby granite and sandstone.[26] A single architrave was congenital of violet sandstone, purportedly sourced from Mentuhotep Ii's temple.[27] This temple, built centuries earlier and found immediately s of Hatshepsut's, served as the inspiration for her design.[28] On its main axis and at the finish of temple, lay the temple's primary cult site, a shrine to Amun-Re, which received his barque each twelvemonth during the Beautiful Festival of the Valley in May.[29] [30] [31] In the south were the offering halls of Thutmose I and Hatshepsut and to the due north was the solar cult courtroom.[32] Outside, ii further shrines were built for Hathor and Anubis, respectively.[33] In total, the temple comprised v cult sites.[34]

The identity of the architect behind the project remains unclear. It is possible that Senenmut, the Overseer of Works, or Hapuseneb, the High Priest, were responsible. It is also likely that Hatshepsut provided input to the project.[x] Over the course of its structure, between the seventh and twentieth yr of Hatshepsut's reign, the temple plan underwent several revisions.[27] A clear example of these modifications is in the Hathor shrine, whose expansions included, among other things, a conversion from a single to dual hypostyle halls.[35] Its pattern was directly inspired by Mentuhotep 2's bordering temple immediately south,[xiii] although its manner of arrangement is entirely unique.[11] For example, whilst the primal shrine of Mentuhotep II's temple was defended to his mortuary cult, Hatshepsut instead elevated the shrine of Amun to greater prominence.[36] [22] Nonetheless, her mortuary cult was otherwise afforded the most voluminous chamber in the temple, harkening dorsum to the offering halls of the pyramid historic period.[36] There are parallels betwixt the temple'south architectural manner and contemporaneous Minoan architecture, which has raised the possibility of an international style spreading across the Mediterranean in this period.[10] [37] Hatshepsut may also be of partly Cretan descent.[37] Overall, the temple is representative of New Kingdom funerary architecture which served to laud the pharaoh and to honour gods relevant to the afterlife.[38]

Architecture [edit]

Terraces [edit]

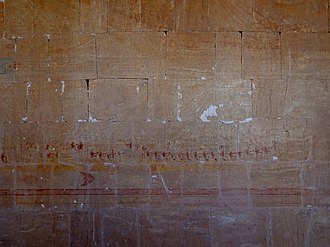

Hatshepsut'south expedition to Punt

The opening feature of the temple is the three terraces fronted by a portico leading upwards to the temple proper, and arrived at by a 1 km (0.62 mi) long causeway that led from the valley temple.[27] Each elevated terrace was accessed by a ramp which bifurcated the porticoes.[thirteen]

The lower terrace measures 120 m (390 ft) deep by 75 grand (246 ft) wide and was enclosed by a wall with a single 2 k (vi.six ft) wide entrance gate at the centre of its east side. This terrace featured two Persea (Mimusops schimperi) trees, two T-shaped basins which held papyri and flowers, and two recumbent king of beasts statues on the ramp balustrade.[39] [40] The 25 m (82 ft) wide porticoes of the lower terrace contain 22 columns each, arranged in two rows,[41] [42] and feature relief scenes on their walls.[24] [43] The south portico's reliefs depict the transportation of two obelisks from Elephantine to the Temple of Karnak in Thebes, where Hatshepsut is presenting the obelisks and the temple to the god Amun-Re. They also depict Dedwen, Lord of Nubia[43] and the 'Foundation Ritual'.[44] The north portico's reliefs depict Hatshepsut as a sphinx crushing her enemies, along with images of fishing and hunting, and offerings to the gods.[43] [45] The outer ends of the porticoes hosted 7.8 m (26 ft) tall Osiride statues.[46] [47]

The heart terrace measures 75 thou (246 ft) deep past 90 m (300 ft) wide fronted by porticoes on the w and partially on the north sides.[45] [13] The west porticoes contain 22 columns arranged in two rows while the north portico contains 15 columns in a single row.[41] The reliefs of the westward porticoes of this terrace are the most notable from the mortuary temple. The south-west portico depicts the expedition to the Land of Punt and the transportation of exotic goods to Thebes. The north-west portico reliefs narrate the divine birth of Hatshepsut to Thutmose I, represented as Amun-Re, and Ahmose. Thus legitimizing her rule both by royal lineage and godly progeny.[43] [45] This is the oldest known scene of its type.[48] Structure of the north portico and its four or five chapels was abandoned prior to completion and consequently it was left blank.[49] [50] The terrace also likely featured sphinxes set up along the path to the side by side ramp,[45] whose balustrade was adorned by falcons resting upon coiled cobras.[51] In the south-west and north-west corner of the terrace are the shrines to Hathor and Ra, respectively.[43] [45] [41]

The upper terrace opens to 26 columns each fronted past a 5.2 m (17 ft) tall Osiride statue of Hatshepsut.[52] [xiii] They are dissever in the centre by a granite gate through which the festival courtyard was entered.[53] [54] This division is represented geographically, besides, equally the southern colossi comport the Hedjet of Upper Arab republic of egypt, while the northern colossi bear the Pschent of Lower Egypt.[54] The portico here completes the narrative of the preceding porticoes with the coronation of Hatshepsut as male monarch of Upper and Lower Egypt.[51] The courtyard is surrounded by pillars, two rows deep on the northward, e and south sides, and three rows deep on the due west side.[13] Viii smaller and ten larger niches were cutting into the due west wall, these are presumed to have contained kneeling and continuing statues of Pharaoh Hatshepsut.[twoscore] [45] The remaining walls are carved with reliefs. The Beautiful Festival of the Valley on the north, the Festival of Opet on the east, and the coronation rituals on the due south.[32] [45] Iii cult sites branch off from the courtyard.[32] The sanctuary of Amun lies west on the main axis, to the north was the solar cult courtroom, and to the south was chapel dedicated to the mortuary cults of Hatshepsut and Thutmose I.[55] [41]

-

Remains of a Persea tree of the lower terrace

-

Balustrade adorned with a Horus statue

-

Punt portico of the middle terrace

-

North portico of the centre terrace

-

Osiride statues of Hatshepsut of the upper terrace

Hathor shrine [edit]

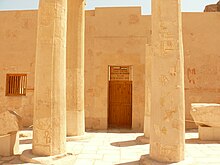

At the south end of the middle terrace is a shrine defended to the goddess Hathor.[56] [43] [45] The shrine is separated from the temple and is accessed by a ramp from the lower terrace, although an culling entrance existed at the upper terrace.[47] [57] [45] The ramp opens up to a portico adorned with four columns conveying Hathor capitals.[56] [53] The walls of the archway contain scenes of Hathor being fed by Hatshepsut.[58] Within are two hypostyle halls, the first containing 12 more columns[53] and the second containing 16 columns.[45] Beyond this are a antechamber containing ii more than columns and a double sanctuary.[45] Reliefs on the walls of the shrine depict Hathor with Hatshepsut, the goddess Weret-hekhau presenting the pharaoh with a Menat necklace, and Senenmut.[45] [53] Hathor holds special significance in Thebes, representing the hills of Deir el-Bahari, and also to Hatshepsut who presented herself every bit a reincarnation of the goddess.[56] [43] Hathor is too associated with Punt, which is the bailiwick of reliefs in the proximate portico.[43]

-

The shrine to Hathor

-

Archway into the Hathor shrine

-

Hathor capital columns

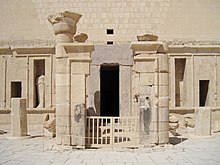

Anubis shrine [edit]

At the n end of the middle terrace is a shrine dedicated to the god Anubis.[33] [43] [45] This shrine is smaller than its counterpart to Hathor in the s.[43] [53] Information technology comprises a hypostyle hall adorned with 12 columns arranged into 3 rows of four, followed by a sequence of two rooms terminating at a pocket-sized niche.[45] [56] Images presented on the walls are of offerings and cult activity, with a relief showing Anubis escorting Hatshepsut to the shrine.[45] The proper name of Anubis was used to designate the heir to the throne, which the Egyptologist Ann Macy Roth associates to the reliefs depicting Hatshepsut's divine nascency.[43]

-

The shrine to Anubis

-

Anubis presented with bounteous offerings

-

Sokaris (Osiris) presented with wine past Thutmose Iii

Amun shrine [edit]

Barque hall of the shrine to Amun

Situated at the back of the temple, on its main axis, is the climactic point of the temple, the sanctuary of Amun, to whom Hatshepsut had dedicated the temple equally 'a garden for my father Amun'.[34] [22] [59] Within, the first chamber was a chapel which hosted the barque of Amun and a skylight that allowed light to flood onto the statue of Amun.[34] [lx] The lintel of the red granite entrance depicts ii Amuns seated upon a throne with backs together and kings kneeling in submission earlier them, a symbol of his supreme status in the sanctuary.[61] Inside the hall are scenes of offerings presented by Hatshepsut and Thutmose I, accompanied by Ahmose and Princesses Neferure and Nefrubity,[62] four Osiride statues of Hatshepsut in the corners,[63] and half-dozen statues of Amun occupying the niches of the hall.[61] In the tympanum, cartouches containing Hatshepsut's proper name are flanked and apotropaically guarded by those of Amun-Re.[64] This bedchamber was the end betoken of the almanac Beautiful Festival of the Valley.[65]

The 2nd bedchamber contained a cult prototype of Amun,[60] [34] [62] and was flanked either side past a chapel.[66] The north chapel was carved with reliefs depicting the gods of the Heliopolitan Ennead and the s chapel with the corresponding Theban Ennead. The enthroned gods each carried a was-sceptre and an ankh. Presiding over the delegations, Atum and Montu occupied the end walls.[67] The third chamber contained a statue around which the 'Daily Ritual' was also performed. It was originally believed to have been synthetic a millennium after the original temple, nether Ptolemy Eight Euergetes, giving it the proper noun 'the Ptolemaic Sanctuary'. The discovery of reliefs depicting Hatshepsut evidence the structure to her reign instead.[68] The Egyptologist Dieter Arnold speculates that it might accept hosted a granite fake door.[34]

Solar cult court [edit]

Altar of the solar cult complex

The solar cult is accessed from the courtyard through a vestibule occupied by 3 columns in the north side of the upper terrace courtyard.[45] [56] The doorjamb of the entrance is embellished with the figures of Hatshepsut, Ra-Horakhty (Horus) and Amun.[62] The reliefs in the vestibule contain images of Thutmose I and Thutmose III.[32] The lobby opens upwards to the main court which hosts a yard altar open to the heaven and accessed from a staircase in the courtroom's westward.[56] [45] [58] There are 2 niches nowadays in the courtroom in the south and west wall, the former shows Ra-Horakhty presenting an ankh to Hatshepsut and the latter contains a relief of Hatshepsut as a priest of her ain cult.[45] Attached to the court was a chapel[due east] which contained representations of Hatshepsut's family.[thirty] In these, Thutmose I and his mother, Seniseneb, are depicted giving offerings to Anubis, while Hatshepsut and Ahmose are depicted giving offerings to Amun-Re.[32]

Mortuary cult complex [edit]

Situated in the south of the courtyard was the mortuary cult complex.[36] Accessed through a vestibule adorned with three columns are two offering halls oriented on an east–westward axis.[70] [32] The northern hall is defended to Thutmose I; the southern hall is dedicated to Hatshepsut.[70] Hatshepsut's offering-hall emulated those found in the mortuary temples of the Quondam and Eye Kingdom pyramid complexes. Information technology measured thirteen.25 m (43.v ft) deep by five.25 m (17.ii ft) wide and had an vaulted ceiling 6.35 yard (20.8 ft) high.[36] Consequently, it was the largest chamber in the whole temple.[71] Thutmose I'due south offer-hall was decided smaller, measuring 5.36 yard (17.half dozen ft) deep by two.65 thou (8.7 ft) broad.[72] Both halls contained red granite faux doors, scenes of animal-sacrifice, offerings and offering-bearers, priests performing rituals, and the owner of the chapel seated before a table receiving those offerings.[32] Scenes from the offering-hall are directly copies of those present in the Pyramid of Pepi II, from the cease of the Sixth Dynasty.[71]

Foundation deposits [edit]

Prior to its construction, the 'stretching of the cord' otherwise known as the 'foundation ritual' was performed.[73] [44] The ritual is depicted in particular on the s portico of the lower terrace. The ceremony opens earlier the goddess Seshat, it follows Hatshepsut and her ka handful besen grains before she offers her temple to Amun-Re. The next scene has been lost, it preceded the endmost scene of the 'Great Offering' to Amun-Re-Kamutef.[44] [74] During the anniversary, the consecration of foundation deposits would accept place,[44] a do that started equally early on as the Third Dynasty of Egypt at the Pyramid of Djoser.[73] There are sixteen known foundation deposits at Hatshepsut's temple, that generally outline its perimeter, and a further 3 at the valley temple.[75] Broadly, pottery, votives, food and ritual offerings, tools, scarabs and seal amulets were deposited into the prepared holes.[73] [76] The titles of Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, and Neferure are incised into some of these items, as are images and names of gods.[73]

-

Travertine vases[f] and lids[1000] retrieved from a foundation eolith

-

Scarab bearing the inscription Mꜣꜥt-kꜣ-rꜥ nb tꜣwy meaning Lord of the Ii Lands, Maatkare

-

Delicately inscribed hammering stone,[h] knot amulet,[i] and msḫtyw adze[j]

Function [edit]

Mortuary complex [edit]

Entrance to the mortuary cult circuitous flanked past columns and the coronation ritual

It has been suggested that Hatshepsut's tomb in the Valley of the Kings, KV20, was meant to exist an element of the mortuary complex at Deir el-Bahari.[80] The arrangement of the temple and tomb conduct a spatial resemblance to the pyramid complexes of the Onetime Kingdom,[81] [82] which comprised five central elements: valley temple, causeway, mortuary temple, master pyramid, and cult pyramid.[83] [84] Hatshepsut's temple complex included the valley temple, causeway, and mortuary temple. Her tomb was built into the massif of the same cliffs as the temple, beneath the dominating summit of El Qurn (489 m (ane,604 ft) AMSL[11]) that caps her tomb, in a sense, like the pyramid capped the tomb of an Sometime Kingdom pharaoh.[85] Further, her tomb lies in-line with the offering hall of the mortuary cult complex.[86] At that place is another analogous relationship, that between the mortuary temple and Karnak and that of the pyramids and Heliopolis.[87] Though KV20 is recognized as the tomb of Hatshepsut, there is dispute over who commissioned its initial construction. Two competing hypotheses suggest that the tomb was built originally during the reign of either Thutmose I or Thutmose II and that Hatshepsut had the tomb contradistinct subsequently with an boosted chamber for her ain burying.[80]

The principal function of the temple was to serve the royal mortuary cults of Hatshepsut and Thutmose I.[22] [34] To fulfill this purpose, a mortuary cult complex was built where offerings could be made for the kꜣ, or spirit, of the king.[34] In the Egyptian formulation, the deceased connected to rely on the same sustenance as the living. In life, the aspects of the soul, the kꜣ, bꜣ and ꜣḫ, were contained in the vessel of the living body. On death, the body was rendered immobile and the soul was able to leave it.[88] In her temple, the offering of nutrient and drink was performed earlier the granite false doors of the offering chapels.[89] [ninety] [32] The mortuary ritual, lists of offerings, and the recipient of the rites were depicted on the east wall of both chapels.[32]

Beautiful Festival of the Valley [edit]

A section of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley relief

The sanctuary of Amun was the cease point of the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, conducted annually, starting at the Temple of Karnak.[65] This commemoration dated back to the Middle Kingdom, when information technology concluded at the temple built past Mentuhotep II.[91] [21] The procession began at the Eighth Pylon at Karnak led past Hatshepsut and Thutmosis III, followed by noblemen and priests bearing Amun's barque, accompanied past musicians, dancers, courtiers and more than priests, and guarded by soldiers.[22] [91] A further flotilla of small boats and the great transport Userhat, which carried the barque, were towed.[91] In Hatshepsut's fourth dimension, the barque of Amun was a miniaturized copy of a transport barge equipped with 3 long carrying-poles borne past six priests each.[92] The effigy of a ram'due south head, sacred to Amun, adorned its prow and stern.[92] [93] In the centre of its hull a lavishly ornamented naos was installed and the statue of Amun, presently bejewelled, cloistered within. The barque likely measured 4.five m (15 ft) in length.[92] The procession crossed the Nile, visited the cemeteries in remembrance, before landing at the valley temple to continue along the 1 km (0.62 mi) long causeway to the temple proper.[22] [34] Halfway up was the barque station, across which the path was flanked by more than 100 sandstone sphinxes upwards to the terraces.[34] [27] This is the oldest attested sphinx avenue, though the practise is thought to date to the One-time Kingdom.[94] The valley temple and barque station were points at which offerings were made and purification rituals conducted.[91] The procession carried on through the archway-gate, upwards the temple's corking ramps, and into the sanctuary where the barque and Amun were kept for a dark earlier existence returned home to Karnak.[91] On this mean solar day, bounteous offerings of food, meat, drink and flowers were presented on tables to Amun, with smaller quantities reserved for the king.[95] On all other days, priests performed the 'Daily Ritual' upon the statues of Amun and Hatshepsut.[96]

Daily ritual [edit]

Before dawn each morning, a pair of priests visited the temple'south well to collect water for transfer to libation vessels. Other priests busied themselves preparing food and potable as offerings to the gods while the caput priest, ḥm-nṯr, visited the pr–dwꜣt to be purified and clothed in preparation for the ceremony. The naos containing the cult image of Amun-Re was first purified with incense. At first light, the caput priest opened the shrine and prostrated himself earlier the god declaring that he had been sent on behalf of the king, while other priests performed recitations. The shrine was purified with h2o and incense and a statuette of Maat was presented to the cult image which was then removed. The statuette was de-clothed, cleared of oil, and placed on a pile of clean sand, a representation of benben. Fresh paint was practical to its eyes, it was anointed with various oils, dressed in new garments of cloth, and provided with accessories. Lastly, its face was all-powerful and sand scattered effectually the chapel before the prototype was returned to its resting place. By now, the god's breakfast offering was presented to him. A final set of purifications were conducted and the doors to shrine closed with the head priest sweeping abroad his footsteps backside him. The nutrient was taken away equally well – they were not physically consumed, the god only partook of their essence – to be re-presented at the chapels of other deities. Each god received essentially the same service. The food was eventually consumed by the priests in the 'reversion of offerings', wḏb ḫt. More than purifying libations were poured and incense burned at the shrines at noon and in the evening. At other times, hymns were sung, apotropaic rituals performed to protect Amun-Re's barque as it voyaged beyond the heaven, and wax or dirt images of enemies destroyed.[97] [98]

Afterward history [edit]

In ancient Egypt [edit]

Proscription of Hatshepsut past Thutmose Three [edit]

Two decades after her death, during Thutmose III'south 40-2nd regnal yr, he decided that all bear witness of her reign as male monarch of Egypt should be erased. His reasons for proscribing her reign remain unclear. This assault against her reign was, withal, short-lived. Two years after it started, when Amenhotep II ascended to the throne, the proscription was abandoned and much of the erasure left half-finished.[99]

There are 3 hypotheses regarding Thutmose 3's motivation. The oldest and most dubious is personal revenge. This hypothesis holds that Hatshepsut usurped the throne every bit sole ruler, relegating Thutmose Three, and consequently he sought to erase her memory. This explanation is unconvincing every bit the proscription was delayed past 2 decades and targeted simply against her reign as king.[100] [101] The second argument is that it was a repudiation of the concept of female kingship. The role of a king was closed to women, and her supposition of the part may have presented ideological problems that were resolved via erasure. This may explain the decision to leave images of her every bit queen intact.[102] [103] The tertiary case assesses the possibility of a dynastic dispute betwixt the Ahmosid and Thutmosid lineages. By expunging her rule from the record, Thutmose Three may take ensured that his son, Amenhotep II, would arise the throne.[101] There is, however, no known Ahmosid pretender.[102]

Several methods of erasure were employed at her temple by Thutmose III in his campaign. The least dissentious were the scratching out of feminine pronouns and suffixes, which otherwise left the text intact. These were commonly used in the Hathor shrine and in the upper terrace. More thorough removal methods included chiselling away, roughening, smoothing, patching or covering over of her prototype and titles. In other places her image was replaced with that of an offer table. Occasionally, her paradigm was repurposed for a member of the Thutmosid family. This was most often Thutmose Two, although infrequently instead her cartouche was replaced with that of Thutmose I or III.[104] The concluding method, and the most destructive, was the obliteration of her statuary in the temple. Workmen dragged the statues from her temple to one of two designated sites, a quarry – a burrow from which fill textile was obtained – and the Hatshepsut Hole. Here, sledgehammers and stone blocks were used to break up the statues which were then dumped into the chosen repositories.[105]

-

Statues of Hatshepsut were targeted for destruction during the proscription

-

The decapitated head from a Hatshepsut statue

-

Erasure of Hatshepsut'due south purple titulary (left)[1000] with Thutmose Three's purple titulary (right)[l]

-

A column re-inscribed with ꜥꜣ-ḫpr-n-rꜥ, Thutmose 2's throne name

-

A cleaved cavalcade with a partial serekh bearing the signs for Rꜥ and mrỉ

Amarna Menstruum to Tertiary Intermediate Period [edit]

Erasure of Amun (right figure) by order of Akhenaten

The temple connected to serve as a site of worship following Thutmose III'due south death. During the Amarna Period, further erasure of the reliefs was inflicted by social club of Akhenaten, albeit the target of this persecution were images of the gods, particularly Amun.[107] Early in his reign, Aten, a solar deity, was elevated to the status of supreme god.[108] [109] The persecution of other gods did not begin immediately, instead reform proceeded gradually for several years earlier culminating in prohibition around his ninth regnal year. The proscription coincides with the ostracization of Horus.[110] [111] These images were restored during the reigns of Tutankhamun, Horemheb, and Ramesses II.[112] [92] The temple was damaged further by an earthquake in the ninth century BC, during the Third Intermediate Period.[107] [113] During this time, between the Twenty-First and Twenty-Fifth Dynasties, the temple was used as a burying basis for priests of the cults of Amun and Montu, also as for members of the majestic family.[114]

Ptolemaic era [edit]

Ptolemaic portico of the festival courtyard

During the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, a stone chapel was built on the center terrace for Asklepios, a god of the Greek pantheon.[107] [27] Later on under Ptolemy Eight Euergetes, the sanctuary of Amun was significantly altered. The cult statue sleeping accommodation was converted into a chapel for Amenhotep, son of Hapu, the Eighteenth Dynasty architect of Amenhotep Iii, Imhotep, the Third Dynasty vizier of Djoser, and Hygieia, the Greek goddess of hygiene.[115] [107] In the barque hall, the two centre niches were filled and the skylight blocked.[115] [63] The sanctuary archway was outfitted with a portico carried by six columns.[63] [107]

Beyond ancient Egypt [edit]

After the Ptolemaic kingdom, the temple was used every bit a site of local worship. Between the 6th and eighth centuries Advertising, a Coptic monastery of Saint Phoibammon was constructed on the temple grounds. Figures of Christ and other saints were painted over the original relief work with the temple. A pilgrim left the latest dated graffito in c. 1223.[116]

Archaeological excavations [edit]

The earliest modern visitor to the temple was Richard Pococke, an English traveller, in 1737. He was followed by François Jollois and Renée Edouard Devilliers, 2 members of Napoleon Bonaparte's expedition, in 1798. The earliest archaeological findings were made effectually 1817 by Giovanni Battista Belzoni and Henry William Beechey, who scavenged the site for artefacts to present to Henry Salt, the British delegate. Another visitor to the site, in 1823–1825, Henry Westcar is credited with the earliest printed reference to the name Deir el-Bahari. In the following decades John Gardner Wilkinson, Jean-François Champollion and Karl Richard Lepsius each visited the site. The earliest pregnant excavations took place in the 1850s and 60s nether Auguste Mariette. Nether his supervision the remains of the monastery Saint Phoibammon were destroyed and the shrines to Hathor and Anubis as well equally the south colonnade of the middle terrace were revealed. During the Egypt Exploration Fund'due south (EEF) trek, under Édouard Naville and his assistant Howard Carter, from 1893–1906, the entire temple was excavated. The seven volumes of Naville'southward work course a primal source for the temple. In 1911–1936, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) funded excavation works under the direction of Herbert E. Winlock. In 1925–1952, a team led by Émile Baraize for the Egyptian Antiquities Service reconstructed significant portions of the temple. Since 1961, the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archeology (PCMA) of Warsaw University in Cairo has been engaged in restoration and consolidation efforts at the site.[117] [27]

The Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Trek was established past Kazimierz Michałowski, after he was approached past the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA). The project was originally constrained to reconstructing the 3rd terrace, but, since 1967, the mission has encapsulated the entire temple. The project is presently directed by Patryk Chudzik. The site is being gradually opened to tourism. Since 2000, the festival courtyard, upper terrace, and the coronation portico have been open to visitors. In 2015, the solar cult court and, in 2017, the sanctuary of Amun were besides opened to visitation. [118] [119]

Panoramic view of the mortuary temple

See also [edit]

- List of ancient Egyptian sites

Notes [edit]

- ^ This is one of many recorded renderings of Ḏsr-ḏsrw. This particular rendering appears in the Hathor and Amun shrines.[1]

- ^ Proposed dates for Hatshepsut's reign: c. 1502–1482 BC,[4] c. 1498–1483 BC,[v] c. 1479–1458 BC,[vi] c. 1473–1458 BC,[7] c. 1472–1457 BC.[8]

- ^ An introduction by the Egyptologists and curators at the Metropolitan Museum of Fine art in New York Catherine H. Roehrig, Renée Dreyfus, and Cathleen A. Keller: 'During this menses Egyptian artists reinterpreted the traditional forms of art and compages with an originality that is exemplified in Hatshepsut's temple at Deir el-Bahri in western Thebes, ane of the great architectural wonders of the ancient world'.[9] A argument by the archaeologist Dieter Arnold: 'A masterpiece of pharaonic temple compages and indeed of architecture earth wide, the building was certainly designed by 1 of the greatest temple builders of ancient Egypt'.[10] A commentary by Zbigniew Szafrański, former director of the Shine Archaeological and Conservation Trek at the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari: 'An explosion of artistic inventiveness past Hatshepsut is exemplified in her temple at Deir el-Bahari. Landscape, terraced compages and sculpture created one of the groovy architectural wonders of the ancient earth. It is a masterpiece of pharaonic temple compages'.[xi]

- ^ Proposed dates for Mentuhotep II'due south reign: c. 2066–2014 BC,[12] c. 2051–2000 BC,[13] c. 2055–2004 BC,[14] c. 2010–1998 BC,[fifteen] c. 1897–1887 BC.[16]

- ^ It is variously referred to as the 'upper Anubis shrine', 'chapel of the parents' and 'chapel of Thutmose I'.[69]

- ^ Tall vase bears sꜥt-rꜥ ẖnmt-ỉmn-ḥꜣt-špśwt ỉr north southward mnnw s n tf s ỉmn ḫft pḏ-šśḥr ḏsr-ḏsrw-ỉmn ỉr due south ꜥnḫ-tỉ translating to 'girl of Re Khnemet-Imen-Hatshepsut made her monument for her father at the time of the stretching of the cord over Djeser-djeseru-Amun so that she may be made to live'. Modest vase bears nṯrt nfr nbt tꜣwy Mꜣꜥt-kꜣ-rꜥ ꜥnḫ-tỉ * ỉmn g ḏsr-ḏsr-w mrỉt translating to 'the proficient goddess, lady of the 2 lands, Maatkare, may she be made to live * dearest of Amun in Djeser-djeseru. Run into also Catherine H. Roehrig'southward translations on pp. 144–145.[77]

- ^ Big lid bears nṯrt nfr Mꜣꜥt-kꜣ-rꜥ ỉr due north southward mnnw s northward tf s ỉmn ḫft pḏ-šśḥr ḏsr-ḏsrw-ỉmn ỉr southward ꜥnḫ-tỉ rꜥ mỉ ḏet translating to 'the good goddess Maatkare, she made her monument for her father Amun at the time of the stretching of the cord over Djeser-djeseru-Amun so that she may be made to live like Re forever'. Small lid bears 2 columns of text facing each other reading nṯrt nfr Mꜣꜥt-kꜣ-rꜥ ꜥnḫ-tỉ * ỉmn ḥr-tp tꜣwy mrỉt translating to 'the practiced goddess Maatkare, may she exist fabricated to live' * 'beloved of Amun, on behalf of the Two Lands'.

- ^ Bearing the inscription nṯrt nfr Mꜣꜥt-kꜣ-rꜥ ỉr n s mnnw s north tf s ỉmn-rꜥ ḫft pḏ-šśḥr ḏsr-ḏsrw-ỉmn ỉr s ꜥnḫ-tỉ translating to 'the good goddess Maatkare, she made her temple for her father Amun-Re at the fourth dimension of the stretching of the cord over Djeser-djeseru-Amun then that she may be made to live'. See also Catherine H. Roehrig'due south translation on p.145.[78]

- ^ Bears her prenomen Mꜣꜥt-kꜣ-rꜥ above and nomen ẖnmt-ỉmn-ḥꜣt-špswt below.[79]

- ^ Bears her prenomen Mꜣꜥt-kꜣ-rꜥ.[79]

- ^ The left one-half of the relief was one time occupied by the Horus, throne, and birth names of Hatshepsut. The top line has been thoroughly obliterated. Of the middle line, the shapes of nsw-bỉty remain just the cartouche does not. Behind information technology the text reads ỉmn-rꜥ mrỉ, meaning 'Love of Amun-Re'. This text appears on the contrary side of the aforementioned line besides. Of the lower line, the glyphs of sꜥ-rꜥ are legible, along with ỉmn, a fragment of ẖnmt-ỉmn-ḥꜣt-špswt.[79]

- ^ The names read: one) Horus: Kꜣ-nḫt-ḫꜥ-grand-wꜣst ; two) Throne: Mn-ḫpr-rꜥ ; 3) Birth: Ḏḥwty-ms nfr-ḫpr [106]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, pp. 230–236.

- ^ a b c Iwaszczuk 2016, p. 49.

- ^ a b Pirelli 1999, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Troy 2001, p. 527.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 104.

- ^ Roehrig, Dreyfus & Keller 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 485.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 290.

- ^ a b Roehrig, Dreyfus & Keller 2005, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d east f Arnold 2005a, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d Szafrański 2014, p. 125.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e f Arnold 2005a, p. 136.

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 483.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 72.

- ^ Redford 2001, pp. 621–622.

- ^ Bryan 2003, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 209.

- ^ Roehrig, Dreyfus & Keller 2005, p. iii.

- ^ Allen 2005, p. 83.

- ^ a b Allen 2005, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e f g Roth 2005, p. 147.

- ^ Arnold 2003, p. 104.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson 2000, p. 176.

- ^ Pirelli 1999, p. 275.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d east f Pirelli 1999, p. 276.

- ^ Bryan 2003, p. 232.

- ^ Roth 2005, pp. 147 & 150.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2000, p. 178.

- ^ Allen 2005, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h i Roth 2005, p. 150.

- ^ a b Arnold 2005a, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b c d due east f k h i Arnold 2005a, p. 137.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, pp. 80–85.

- ^ a b c d Arnold 2005a, p. 138.

- ^ a b Szafrański 2014, p. 126.

- ^ Strudwick & Strudwick 1999, p. 81.

- ^ Pirelli 1999, p. 277.

- ^ a b Arnold 2003, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Arnold 2005a, p. 136, fig 57.

- ^ Pirelli 1999, p. 277, fig 24.

- ^ a b c d e f thousand h i j k Roth 2005, p. 149.

- ^ a b c d Iwaszczuk 2016, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j 1000 l k n o p q r Pirelli 1999, p. 278.

- ^ Szafrański 2018, pp. 377 & 390.

- ^ a b Grimal 1992, p. 211.

- ^ Yurco 1999, p. 819.

- ^ Ćwiek 2014, p. 82.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Szafrański 2007, p. 95.

- ^ Szafrański 2018, p. 377.

- ^ a b c d e Wilkinson 2000, p. 177.

- ^ a b Szafrański 2014, p. 130.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Arnold 2005a, p. 139.

- ^ Arnold 2005a, pp. 139, 137 figure 57.

- ^ a b Bryan 2003, p. 233.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 176 & 178.

- ^ a b Pawlicki 2017, p. 28.

- ^ a b Pawlicki 2017, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Pirelli 1999, p. 279.

- ^ a b c Szafrański 2007, p. 97.

- ^ Pawlicki 2017, p. iv.

- ^ a b Roth 2005, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Pawlicki 2017, pp. 4 & 24.

- ^ Pawlicki 2017, p. 24.

- ^ Pawlicki 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, p. 119.

- ^ a b Pirelli 1999, pp. 278–279.

- ^ a b Szafrański 2007, p. 98.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Roehrig 2005a, p. 141.

- ^ Karkowski 2016, p. 113.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, pp. 51–54.

- ^ Roehrig 2005a, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Roehrig 2005a, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Leprohon 2013, p. 98.

- ^ a b Roehrig 2005b, p. 185.

- ^ Ćwiek 2014, p. 67.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, p. 50.

- ^ Bárta 2005, p. 178.

- ^ Verner 2001, pp. 47–54.

- ^ Ćwiek 2014, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Ćwiek 2014, p. 68.

- ^ Ćwiek 2014, p. 69.

- ^ Muller 2002, pp. i–2.

- ^ Iwaszczuk 2016, p. 132.

- ^ Muller 2002, p. ii.

- ^ a b c d e Pawlicki 2017, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Pawlicki 2017, p. 12.

- ^ Hart 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Kasprzycka 2019, p. 361.

- ^ Pawlicki 2017, p. sixteen.

- ^ Pawlicki 2017, p. 14.

- ^ Thompson 2002, pp. 64–66.

- ^ Teeter 2001, pp. 341–342.

- ^ Dorman 2005, pp. 267–269.

- ^ Dorman 2005, pp. 267.

- ^ a b Roth 2005b, p. 281.

- ^ a b Dorman 2005, p. 269.

- ^ Robins 1993, pp. 51–52, 55.

- ^ Roth 2005b, pp. 277–279.

- ^ Arnold 2005b, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Leprohon 2013, pp. 99–100.

- ^ a b c d eastward Arnold 2005c, p. 290.

- ^ Hart 2005, pp. 34 & 36.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 227.

- ^ van Dijk 2003, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Schlögel 2001, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Szafrański 2007, p. 94.

- ^ Szafrański 2018, p. 385.

- ^ Szafrański 2007, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Pawlicki 2017, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Arnold 2005c, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Arnold 2005c, pp. 291–293.

- ^ Szymczak 2019.

- ^ Pawlicki 2007, 1960.

Sources [edit]

- Allen, James P. (2005). "The Office of Amun". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 83–85. ISBNane-58839-173-six.

- Arnold, Dieter (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN978-1-86064-465-8.

- Arnold, Dieter (2005a). "The Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 135–140. ISBN1-58839-173-vi.

- Arnold, Dorothea (2005b). "The Destruction of the Statues of Hatshepsut from Deir el-Bahri". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. pp. 270–276. ISBNi-58839-173-6.

- Arnold, Dorothea (2005c). "A Chronology: The Afterward History and Excavations of the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. pp. 290–293. ISBN1-58839-173-half dozen.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2005). "Location of the Quondam Kingdom Pyramids in Arab republic of egypt". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 15 (2): 177–191. doi:10.1017/s0959774305000090.

- Bryan, Betsy M. (2003). "The 18th Dynasty before the Amarna Period (c. 1550–1352 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Arab republic of egypt. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press. pp. 207–264. ISBN978-0-19-815034-iii.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-05074-3.

- Ćwiek, Andrzej (2014). "One-time and Middle Kingdom Tradition in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari". Études et Travaux. Instytut Kultur Śródziemnomorskich i Orientalnych. 27: 62–93. ISSN 2449-9579.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Consummate Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN0-500-05128-3.

- Dorman, Peter (2005). "The Proscription of Hatshepsut". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 267–269. ISBNone-58839-173-6.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated past Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN978-0-631-19396-8.

- Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Lexicon of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN0-415-34495-vi.

- Iwaszczuk, Jadwiga (2016). Sacred Mural of Thebes during the Reign of Hatshepsut: Regal Construction Projects. Vol. 1. Warsaw: Instytut Kultur Śródziemnomorskich i Orientalnych Polskiej Akademii Nauk. ISBN978-83-948004-2-0.

- Karkowski, Janusz (2016). "'A Temple Comes to Being' : A Few Comments on the Temple Foundation Ritual". Études et Travaux. Instytut Kultur Śródziemnomorskich i Orientalnych. 29: 111–123. ISSN 2449-9579.

- Kasprzycka, Katarzyna (2019). Zych, Iwona (ed.). "Reconstruction of the bases of sandstone sphinxes from the Temple of Queen Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari". Polish Archæology in the Mediterranean. 28 (2): 359–387. doi:10.31338/uw.2083-537X.pam28.2.20. ISSN 2083-537X.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Proper noun: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Writings from the ancient globe. Vol. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN978-1-58983-736-2.

- Muller, Maya (2002). "Afterlife". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Organized religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN0-nineteen-515401-0.

- Pawlicki, Franciszek (2007). "History of PCMA enquiry in Egypt". Polish Middle of Mediterranean Archeology, University of Warsaw. Retrieved Baronial 9, 2021.

- Pawlicki, Franciszek (2017). The Principal Sanctuary of Amun-Re in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari (PDF). Warsaw: Shine Eye of Mediterranean Archeology, University of Warsaw. ISBN978-83-94288-7-iii-0.

- Pirelli, Rosanna (1999). "Deir el-Bahri, Hatshepsut temple". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archeology of ancient Egypt . London; New York: Routledge. pp. 275–280. ISBN978-0-203-98283-nine.

- Redford, Donald B., ed. (2001). "Egyptian King List". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Arab republic of egypt, Volume three. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 621–622. ISBN978-0-19-510234-5.

- Robins, Gay (1993). Women in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN0-674-95469-6.

- Roehrig, Catharine (2005a). "Foundation Deposits for the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 141–146. ISBN1-58839-173-6.

- Roehrig, Catharine (2005b). "The Two Tombs of Hatshepsut". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. pp. 184–189. ISBN1-58839-173-6.

- Roehrig, Catharine H.; Dreyfus, Renée; Keller, Cathleen A. (2005). "Introduction". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 3–seven. ISBNane-58839-173-6.

- Roth, Ann Macy (2005). "Hatshepsut's Mortuary Temple at Deir el-Bahri: Architecture as Political Argument". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 147–157. ISBNane-58839-173-6.

- Roth, Ann Macy (2005b). "Erasing a reign". In Roehrig, Catharine (ed.). Hatshepsut From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 277–283. ISBN1-58839-173-half-dozen.

- Schlögel, Hermann (2001). "Aten". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 156–158. ISBN978-0-19-510234-5.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-815034-iii.

- Strudwick, Nigel; Strudwick, Helen (1999). Thebes in Egypt: A Guide to the Tombs and Temples of Ancient Luxor (1st. publ. ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN0-8014-3693-1.

- Szafrański, Zbigniew Eastward. (2007). "Deir el-Bahari: Temple of Hatshepsut". In Laskowska-Kusztal, Ewa (ed.). Lxx Years of Polish Archaeology in Arab republic of egypt (PDF). Warsaw: Polish Center of Mediterranean Archæology, Academy of Warsaw. ISBN978-83-903796-ane-half-dozen.

- Szafrański, Zbigniew East. (2014). "The Exceptional Creativity of Hatshepsut". In Galán, José Thousand.; Bryan M., Betsy; Dorman, Peter F. (eds.). Creativity and Innovation in the Reign of Hatshepsut. Chicago, IL: Oriental Institute of the Academy of Chicago. ISBN978-1-61491-024-iv.

- Szafrański, Zbigniew East. (2018). Zych, Iwona (ed.). "Remarks on majestic statues in the class of the god Osiris from Deir el-Bahari". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 27 (two): 375–390. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0013.3309. ISSN 2083-537X.

- Szymczak, Agnieszka (Apr 10, 2019). "Deir el-Bahari, Temple of Hatshepsut". Smooth Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw. Retrieved August ix, 2021.

- Teeter, Emily (2001). "Divine Cults". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume i. Oxford: Oxford University Printing. pp. 340–345. ISBN978-0-19-510234-5.

- Thompson, Stephen East. (2002). "Cults: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 62–71. ISBN0-19-515401-0.

- Troy, Lana (2001). "Eighteenth Dynasty to the Amarna Menstruum". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Arab republic of egypt, Book 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 525–531. ISBN978-0-nineteen-510234-5.

- van Dijk, Jacobus (2003). "The Armana Menses and the Later on New Kingdom (c.1352–1069 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Arab republic of egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 265–307. ISBN978-0-19-815034-3.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Arab republic of egypt'south Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN978-0-8021-1703-8.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Arab republic of egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-05100-9.

- Yurco, Frank J. (1999). "representational evidence, New Kingdom temples". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archæology of ancient Egypt . London; New York: Routledge. pp. 818–821. ISBN978-0-203-98283-ix.

Further reading [edit]

- Mariette, Auguste (1877). Deir-el-Bahari: documents topographiques, historiques et ethnographiques, recueillis dans ce temple pendant les fouilles exécutées par Auguste Mariette-Bey. Ouvrage publié sous les auspices de Son Altesse Ismail Khédive d'Egypte. Planches (in French). Leipzig: Heinrichs.

- Naville, Édouard (1895–1909). The Temple of Deir el-Bahari . Vol. I–VI. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

- Kleiner, Fred (2021). Gardner's Art Through the Ages : The Western Perspective. Vol. I. Belmont: Wadsworth.

- Karkowski, Janusz (2003). The Temple of Hatshepsut : the solar circuitous. Warsaw: Neriton.

- Szafrański, Zbigniew (2001). Queen Hatshepsut and her temple 3500 years later on. Warsaw: Agencja Reklamowo-Wydawnicza A. Grzegorczyk.

External links [edit]

- Polish-Egyptian Archaeological and Conservation Mission at the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari

- All Polish Deir el-Bahari Projects

- Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully bachelor online as PDF), which contains material on Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut (run across alphabetize)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortuary_Temple_of_Hatshepsut

0 Response to "Why the Death Rate Was So High in Hatshepsut's Family?"

Post a Comment